All I want for Christmas is some healthy disagreement; or, Can we avoid partisan sorting in Canada?

Here’s a potent statistic: Since the 1960s, the number of Americans who say they’d be upset if their children married someone who supports the opposite political party than the one they endorse has grown from around 5% to around 33% for Democrats and 50% for Republicans. So pretty much an order of magnitude. Imagine bringing your new beau home to meet your parents of the opposite political stripe, all the while dreading the inevitable question.

This statistical trend mirrors a general pattern of partisan sorting and hardening of party lines that has been on the rise in the United States for several decades. Back in the 1950s, it could be hard to tell the Democrat and Republican parties apart, and people “split tickets” all the time (voting for one party at the national level, and the other at the state level). The odds of that happening today, even in the years leading up to the Trump presidencies, are in the ballpark of a Maple Leafs cup victory.

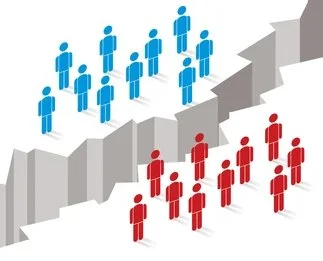

The history of how this “great sorting” happened in the U.S. is an important one, with lessons we should heed here in Canada. NY Times columnist and podcaster Ezra Klein surveys it pretty well in his 2020 book Why We’re Polarized, if you want to go on that ride. [1] But suffice it to say that the trend over the past few decades is very clear in the survey data. Supporters of America’s two parties have become more ideologically distinct from each other and more internally homogenous (i.e. less internal diversity). Fewer American voters are persuadable (meaning a decline in swing voters), and American partisans dislike the other side a whole lot more than they used to.

I read Klein’s book[2] in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Freedom Convoy occupation, when tensions were at a fever pitch. So far, Canada has mostly been able to avoid the worst of the partisan morass that has been consuming our American neighbours. But there are troubling warning signs, and the pressure cooker of the pandemic pushed them further to the surface. While things have settled down a bit and we’re more united around a shared national challenge, those tensions are lurking not far below the surface.

Taking in the history of U.S. sorting into us/them camps, I wondered if we Canadians are so different, and whether our multi-party political landscape is insulating us from a slow drift into a similar state of affairs. In Canada, rather than being forced to choose between two options (i.e. polarities), voters have three+ national political options (four+ if you’re in Quebec). Each of the parties must try to hold together a coalition and be mindful of their flanks, as there’s always another party there waiting to pick up the voters you alienate.

The Liberals under Mark Carney are on a tear these days with natural resource development, but are eventually going to have to consider their left flank lest they hand the NDP and the Greens a bunch of votes back. The Conservatives under Pierre Poilievre are giving more attention to centrist voters that they need in order to form government. The NDP are in rebuild mode and thinking about whether they can sustain a coalition of working-class socially moderate voters together with environmental and social justice advocates.

Political parties tend to be filled with ideologically-inclined types who read John Maynard Keynes or Milton Friedman at bedtime, but they recognize that the majority of voters are in the middle of the bell curve. When you have multiple parties, you need to convince those centre-ish voters that you’re the best option. But when you have only two parties, you only need to convince them that you’re less awful than the other crew. And that involves not only selling your own party, but also convincing voters that the other crew is awful – sometimes more the latter than the former.

Things are looking a fair bit less multi-party on the national level in Canada these days, and in many provinces. While the fate of the federal NDP remains to be seen, voter preferences have not budged much since the last election, and there’s reasonable speculation that we’ll be in a mainly two-party system for the next election cycle or two.

Maybe we’ll be fine, relatively speaking. Maybe there’s just something in our cool, clean Canadian water that sets us apart from our American neighbours. Maybe our more reserved, less combative culture will keep a leash on our two biggest political parties, lest they alienate median voters. But I’d suggest we should be mindful that polarization can be a long-term process, and most importantly that it has a feedback-loop quality.

Once the polarizing process starts, it reinforces its own divisions. Party A needs to differentiate itself from Party B, and convince voters that their product is better and the others’ inferior. Over time, the Venn diagram of overlap between them turns into two distinct polarities. The ideas and proposed policies of Party A really are a threat to the values of Party B followers, not just rhetorical distinctions without differences.

As polarization deepens, it also tends to drive greater animosity towards supporters of the other side. It’s not just about disagreeing on certain policies or issues (health care reform, gun control, emissions caps, etc.). It becomes about judging what kind of people the folks in the other camp are. Selfish capitalists. Naïve tree huggers. Gun nutballs. Woke cancellers.[3] Humanity and nuance take a back seat to simplistic-yet-satisfying labels, and the warm embrace of self-reinforcing social echo chambers.

Brian Mulroney offered many words of praise for John Turner upon his passing, despite a heated political rivalry and having gone head-to-head in the most epic election debate in modern Canadian history. Jean Chretien spoke with Brian Mulroney several times while he fought terminal illness. Do you think Justin Trudeau is going to attend Pierre Poilievre’s funeral? Or that Pierre will ring up Mark Carney on his deathbed? Perhaps that’s a good litmus test of how we’re doing as a country. Or our willingness to throw a great wedding party if our kid falls in love with the other side.

May we see more peace on earth…merry Christmas.

[1] There are two related aspects to sorting – into party alignment and into geographies. In decades past, the Republicans had more progressive members, and Democrats had a solid conservative-leaning wing. This has shifted over time – for example, Joe Biden was once against abortion rights, which is today unthinkable on the blue side. Geographically, there’s growing evidence that more Americans are choosing where they live in part based on political alignment.

[2] By “read”, I mean listened to the audiobook while chopping firewood. He’s a great reader – highly recommended.

[3] I took an e-stroll today through a heated debate about EVs in a Facebook thread. Actually a fair amount of good data provided, but apparently the term “retard” is back in fashion.